“We still hope – those who were there – the living and the dead – that the vision of peace we lived during those few rare hours may be made real and everlasting.” Henry Williamson

On Touching Landscapes, we would like to touch on the true essence of Christmas. As the festive season for 2014 approaches and many families may be planning to share precious time with their loved ones, we have a most moving story to share with you of goodwill and in the hope for peace everlasting, lest we forget…

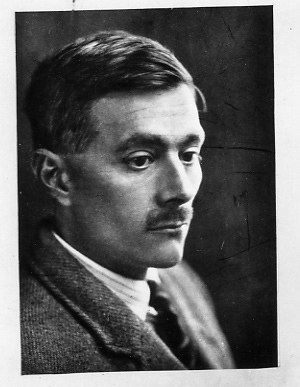

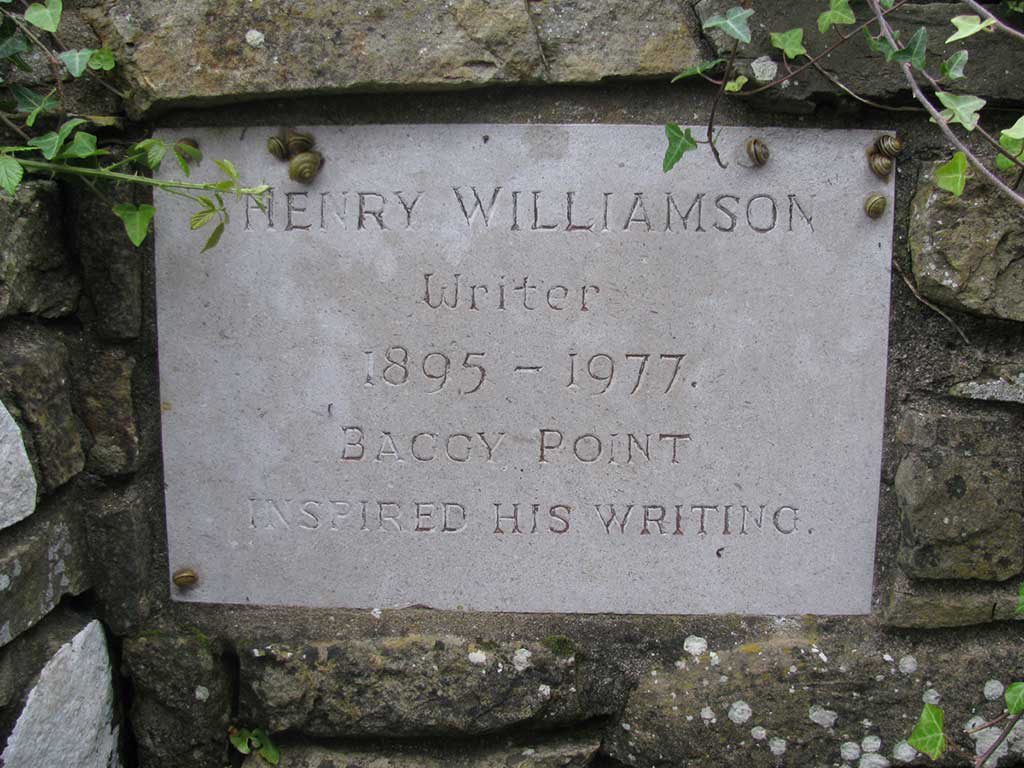

One hundred years ago, Henry Williamson, one of England’s most acclaimed nature writers, best known for his award-winning novel, Tarka the Otter, wrote a letter to his mother from the wet and frozen trenches in the front line of World War I on Christmas Eve.

As the mother of two grown up sons, I can’t begin to imagine how I would feel about my sons being at war. My heart goes out to mothers all around the world who maintain a smiling heart while their sons bravely endure the unthinkable horrors of being in live battle.

In this spirit, I bring you the full and moving account written by Henry Williamson, first published in The Daily Express, on Christmas Eve, Friday, 24 December 1937, and can be found on the Henry Williamson Society website

After his account, I will reveal why the writing from a pen of long ago, from a man with whom I would have enjoyed conversations on so many of his writings, means so much to me.

But for now, let’s set the scene…

One still moonlit night as Henry sits in the granary of his Norfolk farm, the geese flying overhead bring back the vivid memory of one very special Christmas Night in 1914. As his little children sleep warm and snug in a loft on a heap of sacks and rugs, in the peacefulness of night, Henry is moved to retell his experience of a miraculous cease-fire that took place in the trenches in France in the No Man’s Land between German and English soldiers.

He wrote…

“It is Christmas again, and I have a rendezvous in ancient moonlight, with you and you and you, unknown comrades of that first Christmas . . . when for myself and my friends a miracle broke into the near-hopelessness of our youthful lives.

The human facts of that marvellous and (in retrospect) poignantly beautiful time still live, for my generation, with the hope that its knowledge-feeling may increase, that eventually all men in Europe will be inspired by its truth. A long time ago, Christmas 1914 – twenty-three years ago – nearly a quarter of a century.

For weeks we had lived in flooded trenches. The Germans were eighty yards away. Our trench was enfiladed; we lost many men, shot by snipers. Night after night since the tailing-off of the battle for Ypres we had toiled on the parapets, filling sandbags with clayey mud; squelched through the muddy lagoons of woodland tracks, carrying rations, duckboards, pumps, ammunition.

We were volunteers, rushed out to help General French’s shattered Expeditionary Force. A few weeks before we had been schoolboys, bank clerks, undergraduates, medical students. Now our lives were ravaged. Some of us (the young ones who thought of their mothers) were near to despair. We were without hope, without horizon.

At first trench life had been interesting, even enjoyable. It was fun cooking our own bacon and making tea in the wood, while shrapnel cracked overhead; good sport stalking the wild geese in the marshes; satisfying to feel the soft hairs of our unshaven chins. The regulars were decent chaps, heroes of Mons.

But the rains fell, and the trenches filled almost waist-high. After a few days we could scarcely move our legs; nor did we seem to need food. At night we dragged ourselves out of the ditches, and moved about, uncaring of bullets aimed at random in the dark.

All night we worked: carrying parties, pumping fatigues, parapet-building; at dawn we slid into water again, and set ourselves to endure the grey daylight. Even now, so long afterwards, when I hear the rain on the tiles overhead, the ghost of that time makes me draw the blankets closer round my neck.

On Christmas Eve of 1914 we were in the support line, about 200 yards inside Ploegsteert Wood. It was freezing. Our overcoats were stiff as boards, our boots were too hard to remove, but we rejoiced. The mud was hard, too!

Also, happy thought, we would be able to sleep that night – inside a new blockhouse of oak boughs and sandbags called Piccadilly Hotel. No bed but the cold earth, no blankets even; but sleep. Sleep!

Also, happy thought, we would be able to sleep that night – inside a new blockhouse of oak boughs and sandbags called Piccadilly Hotel. No bed but the cold earth, no blankets even; but sleep. Sleep!

Then came a message from brigade headquarters, brought, I think, by Second Lieutenant Bruce Bairns father, of the Warwicks. Wiring parties were required in No Man’s Land all night. And there would be a moon.

We would have to work only fifty yards from the German machine-guns in the White House opposite the eastern edge of the wood. Two hours later we filed out of the dark trees, into the naked, moonlit terror of No Man’s Land, holding shovels beside our faces, in hope of protection against the expected mortar-blast. The moon was high and white among frozen cloudlets. We were visible.

Someone slipped, with a clank of spade or rifle. We flung ourselves on our faces. We waited. The battlefield was as silent as the moon. For an hour we worked in silence, in a most mysterious soundlessness. What had happened?

We began to talk naturally as we drove in stakes, and pulled out concertinas of prepared wire. There was no rifle-fire either up or down the line, from way up north beyond Ypres to south beyond Armentières and the French Army.

At midnight we heard laughing as we worked. We heard singing from the German lines – carols whose tunes we knew. I noticed a very bright light on a tall pole, raised in their lines. Down opposite the East Lancs trench, in front of the convent, a Christmas tree, with lighted candles, was set on their parapet.

The unreal moonlight life went on, happily.

Cries of, ‘Come over, Tommy! We won’t fire at you!’

A dark figure approached me, hesitatingly. A trap? I walked towards it with bumping heart. ‘Merry Christmas, English friend!’ We shook hands, tremulously. Then I saw that the light on the pole was the morning star, the Star in the East. It was Christmas morning.

All Christmas Day, grey and khaki figures mingled and talked in No Man’s Land. Picks and spades rang in the hard ground. It was strange to stare at the dead we had only glimpsed, swiftly, from the trenches. The shallowest graves were dug, filled, and set with crosses knocked together from lengths of ration-box wood, marked with indelible pencil. ‘For King and Country.’ ‘Für Vaterland und Freiheit.’ Fatherland and Freedom!

Freedom? How was this?

We were fighting for freedom, our cause was just, we were defending Belgium, civilisation. These fellows in grey were good fellows, they were – strangely – just men like ourselves.

How can we lose the war, English comrade? Our cause is just, we are ringed with enemies, the war was thrust on us, we are defending our parents, our homes, our German soil.’

A most shaking, staggering thought: that both sides thought they were fighting for the same cause! The war was a terrible mistake! People at home did not know this!

Then the idea came to the young and callow soldier that if only he could tell them all at home what was really happening, and if the German soldiers told their people the truth about us, the war would be over. But he hardly dared to think it, even to himself.

Then the idea came to the young and callow soldier that if only he could tell them all at home what was really happening, and if the German soldiers told their people the truth about us, the war would be over. But he hardly dared to think it, even to himself.

The next day was quiet, and the next. Waving hands from the trenches by day; singing and reflected blaze of trench bonfires at night. It was a lovely time.

On the third afternoon came a message from the Germans. ‘At midnight our staff officers visit, and we must fire our automatic pistolen, but we will fire high, nevertheless please keep undercover.’

At 11 p.m. – Berlin midnight – we saw the flashes going away into the air.

Two days later an Army Order came from G.H.Q., to the effect that men found fraternising with the enemy would be court-martialled, and, if found guilty, would suffer the death penalty.

And again in that place the Véry lights soared over No Man’s Land at night, and bullets cut showers of splinters from the trees, and sometimes human flesh and bone. So Hope sank into the mud again, but did not die.

.…The geese cry as they pass high under the moon, flying for the marshes, my little children stir in their sleep, and the morning star of Hope, of the wise men in the story is rising again.”

Bless you, dear Henry, and you and you, unknown soldiers, let us remember the spirit of peace at Christmas as those of us who are so fortunate to live in a country where we can sit at the same table and toast to our friends and loved ones, past and present…May Peace and Health be with you everlasting!

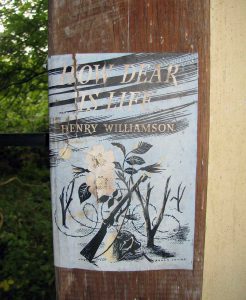

For a brand new collection of Henry Williamson’s books now available as eBooks, please visit the Henry Williamson Society – also to view photos and gain a more thorough background to Henry’s prolific writing career.

Now for my personal reason for introducing Henry’s writing on my travel blog…

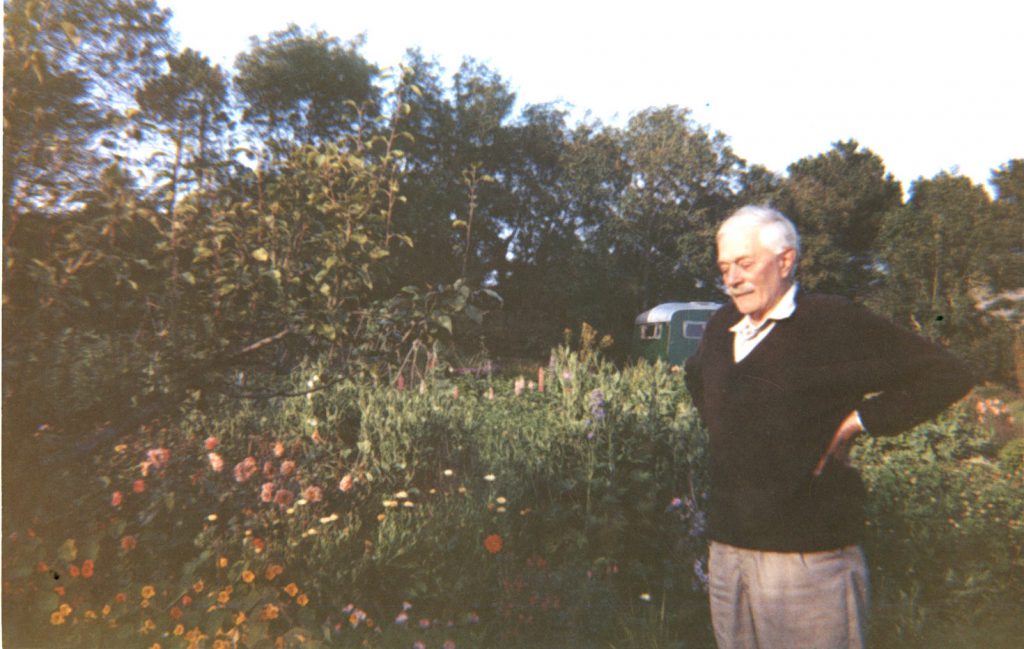

It was in Melbourne, in 2003, when I first met Harry Williamson, Henry’s youngest son, and was introduced to Tarka the Otter, the book and the music! Six years later, in 2009, Harry and I were travelling back to Tarka Country in North Devon to visit Harry’s childhood home, and Henry’s writing hut on the same small plot of land at Ox’s Cross. We also took a detour to visit my own home town near the standing stones of Stonehenge.

Our team consisted of Producer Harry, visually-impaired project coordinator (me) and my fourteen-year-old son, Mike as sighted guide and extra cameraman!

Our team was there to take film footage and interview people for the Tarka Project which later became known as, Precious Music, Precious Water.

It was an exciting and unusual collaborative venture, rich with story, culminating in a World Premiere Concert!

In 2015, I hope to take you behind the scenes of our Tarka Revisited travel experience from excerpts of my diary as part of a new series where the Williamson and Steel family storytelling all began…

DVD Film Precious Music, Precious Water

You can get your own copy of the DVD set to Harry Williamson and Anthony Phillips original symphonic music, featuring film of Devon and Australia,

Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Maribel Steel

Photography Copyright © 2014 Harry Williamson