Our thanks to Ramona Mandy for getting in touch and offering her travel story and photos. Ramona’s reflections on the ingredients required for successful guided travel is a reminder of the tireless team work required when travelling overseas as a blind person.

When I consider the question, what are the issues around travelling as a blind person? I find the answer contains many ‘it depends’ type statements. My own experience and observation of travelling as a blind person comes from the perspective of someone who is totally blind and has lost sight gradually over 25 years.

So I have a good recollection of colours, images and such things as the visual effects of sunlight in certain situations. I have well developed orientation and mobility skills, using a guide dog as my primary mobility aid and can readily use sighted guide techniques.

I have traveled extensively, both interstate and abroad, for education, work and leisure. But it is travelling overseas on holidays that I have felt the greatest impact of my blindness, particularly on visits to Sri Lanka and France.

My partner, John, is usually my sighted guide when we’re overseas and I found the essential key to successful travel is good team work in the form of good verbal and physical communications. We found that we had to develop an extensive vocabulary to accommodate the wide variety of steps that we encountered in Sri Lanka: as in our climb up the 1200 steps to Sigiria, a huge rock with an ancient palace perched on high. Each step was carved in stone, Each step we took had to allow for a different combination of width, depth, height and textural surface. John’s communication had to be concise so I knew where to place my foot next, and although this made the climb easier, I was still pooped on reaching the top.

It’s important to recognise that sighted guide work is demanding on the concentration required by both team members. I would sometimes offer to wait for John somewhere while he went to look at something, buy something or just have a walk around without me hanging off his elbow. John also catered at those times when I was tired by allowing for a greater margin of error when navigating through a busy environment.

I discovered too, when I was focused on doing something with one hand, the other hand had a mind of its own. Several times I would hitch up my socks or adjust my shoulder bag with my left hand, and unknowingly, to the discomfort of my guide, my right hand was tightening on John’s arm.

Seen as a Curiosity

In Sri Lanka, seeing blind people on the street or in public places was not a common sight so I was seen as a curiosity and attracted a lot of open stares. People expressed much puzzlement in how I could be a Westerner and still be blind.

There was little understanding that not all eye conditions are curable. Some people had seen their neighbours benefit from glasses or cataract removal operations and encouraged me to investigate possible medical treatments. I thanked them for their concern and explained how my eyesight was not repairable.

France – a feast for the senses

In France, this was not an issue. Instead, the challenge was to keep up with a busy tour itinerary and to survive with the miniscule amount of French that I had learned. This was where my Braillenote came in extremely handy. I was able to use my notetaker to search for information and as I had completed an intensive five week French course for travellers prior to departing Australia, it meant that I could look up phrases as needed.

Having some knowledge of French and ready access to a braille phrase book created a sense of equality for us, and an opportunity for me to contribute to our getting around.

People who are blind or vision impaired will vary in what faculties they have chosen to maximise for taking in information. I like to use all my senses and have very fond memories of Paris because the city was a sumptuous feast for all my keen senses.

Walking through the streets, the scent of perfume or cologne as people passed by was wonderful. Flower shops and rose vendors at street corners added to the delicious scent, breathing it in deeply as we moved on.

Sampling the fine food and wine meant that my taste buds knew we were on holidays. As I bustled down the narrow streets, I felt the brush of a soft scarf or a coat as others rushed by. The sounds of music coming from cafes and buskers added extra delightful stimulation.

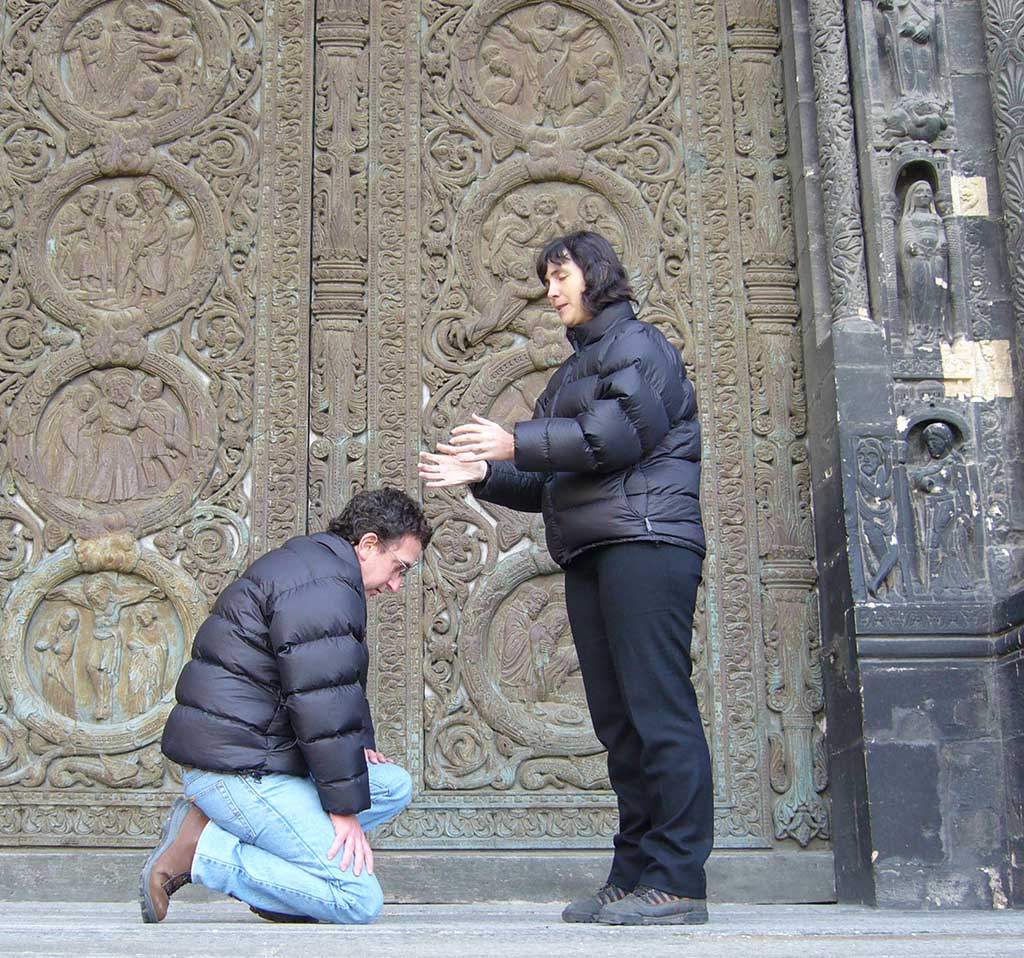

Feeling the sites of France

Vision is by far the dominant sense for most people and as such, tourist activities revolve around seeing, watching and viewing what a place has to offer. I don’t find this an impediment providing I am with someone who can describe the scene well.

Vision is by far the dominant sense for most people and as such, tourist activities revolve around seeing, watching and viewing what a place has to offer. I don’t find this an impediment providing I am with someone who can describe the scene well.

I think the vision-impaired person needs to give advice to their guide as to what constitutes a balanced description as a good description is not necessarily a detailed one.

Some places where John and I visited had model replicas of the real thing: and I always got a better idea of the shape and size by feeling these objects. When visiting one of the grand Chateaux in France, the gift shop had a wooden model and I was able to grasp its unusual features as it had a bridge spanning a river that also supported the medieval building.

When in a museum or a gallery, I like to inquire at the front desk as to what I might be allowed to touch. Most staff are very obliging and will point out what I can or can’t feel, and explain why. In return, I make sure I have clean hands, remove my rings and bracelets, and take extra care when feeling the valuable items.

There is a lot to be said for prearranging tours with galleries and museums as some offer specialised tours for vision-impaired people with having prior notice.

At the Rodin museum, for example, they had a tour guide who showed me how to touch the sculptures in order to get the best sense of the artist’s intensions. Feeling an object is one thing, being shown how to move your fingers and palms gives a greater sense of the overall movement and shape conveyed in the artwork.

One of the disadvantages of travelling in an unfamiliar environment as a blind person is that you can’t go and do your own thing very easily. Your sighted  companions are restricted too.

companions are restricted too.

It would have been nice in France if John could have spent a day pursuing his own interests such as visiting Roman ruins alone without feeling he had left me behind. Similarly, I would have enjoyed being left to my own devices exploring clothing shops independently as I didn’t feel I could put him through the boredom of retail therapy in helping me.

On longer trips, we have fewer times apart from each other than when at home. This doesn’t result in conflict but it means John and I have to negociate more and compromise in ways sighted couples don’t have to while travelling together.

Blindness Shapes How I Travel

There is a lot more of Australia and the rest of the globe that I would like to see. My blindness only shapes how I travel and I have reaped the benefits of organised tours with their friendly and informed tour guides. Walking the sites is far more inspiring for me than to be sitting on a coach that whizzes past sites to the sounds of oohs and ahs from other passengers.

As John and I work to improve the success of our travels, I find being adventurous, organised and adaptable are the ingredients for reducing those little inconveniences we faced as a team viewing the world together.

Story & Photos © 2013 Ramona Mandy

Melbourne, Australia.

You might also like to read other stories from Europe on a White Stick:

Inhaling History, Touching time